I began writing poems, I think, as a way to recapture the Iranian landscape of my childhood and early youth, resulting over the years in something of a chronicle of a soul’s interaction with the spirits of place, what I came to call inner and outer weather. My poems are ritual soundings, in the ancient oral tradition, for the bones and colors of experience, which is to say, they are written to be heard – sound paintings, sounded-out stories, and sometimes songs.

When I was 19 and recuperating from a motorcycle accident in France, I visited, on crutches, the Picasso Retrospective in Paris and was intrigued by his different periods displayed in different rooms; and I think the various sections of my primary work, Bone-Songs and Sanctuaries, are roughly equivalent to different “rooms,” not necessarily chronological but psychically ordered into a kind of plot or journey.

I have recorded this rather long work in large part because I believe that the sound in the air is essential to the authentic form of a poem, the “body” that is breath and timing and the movement of the tongue. I once suggested that we recognize art largely in terms of its edges, and that if I were an American Indian delineating the edges of poetry according to the points of the compass, I would put Song at the top, Dance at the bottom, vernacular speech in the east, and prose in the west. Press any edge, and you have the start of something. Pressure any two or three and the river gods bless you.

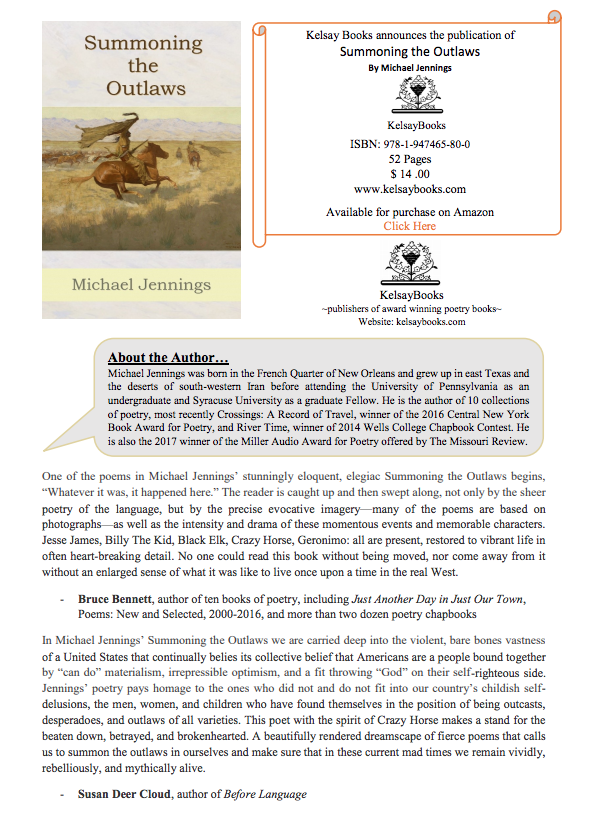

Latest Release

Award-winning poet discusses his new collection “Summoning the Outlaws”

“Summoning the Outlaws” press release